For centuries, American distillers have aged whiskey in warehouses with styles ranging from converted barns to ornate, custom-built brick buildings. But as the whiskey industry in America began to grow, the warehouses became increasingly simple: austere, wood-frame structures with corrugated metal sides and roofs, filled with basic ricks that hold stacks of barrels.

The shift toward simplicity was likely brought on by reduced costs and increased efficiency, says Donald Blincoe, president of Buzick Construction Co., a leading builder of rickhouses since 1937. But, it turned out that the more basic buildings held another advantage soon discovered by distillers: the thin metal roofs and walls resulted in more drastic temperature changes, which had a positive effect on the flavor of the spirit inside.

With only thin metal separating it from Kentucky’s four seasons, the barrels were more “susceptible to temperature changes that improve the whiskey,” says Blincoe, whose firm has partnered with Heaven Hill Distillery for decades.

SIZE MATTERS MORE THAN LOOKS

Most rickhouses are modest structures: rectangular buildings typically of seven stories, usually painted white or black. But these silent, idle storage spaces serve unheralded roles in the myriad chemical changes occurring within the oak.

Barrels stored on the highest floors endure the summer’s worst heat, which leads to more water evaporation and higher proofs. On the lowest floors, where temperatures are much cooler, the reverse happens: barrels often lose more alcohol than water, and proofs drop. The moderate temperatures of the middle floors form a sweet spot where maturation is most balanced.

“We use all the whiskey we make across our portfolio, so one day we’ll mingle it from a mix of barrels from every floor,” says Mike Sonne, Heaven Hill’s Process Engineer and 38-year company veteran. “We’ll also pull barrels from multiple rickhouses to get a good range and balance of flavors for every batch.”

AIR APPARENT

Constant air circulation throughout the structure is crucial to uniform whiskey aging, and Blincoe says it will also keep the rickhouse’s wood structure drier as well. Airflow is often as much a matter of geography as rickhouse design. Buildings located on a bluff or hill benefit from regular breezes, while those in lower locations experience slower maturation.

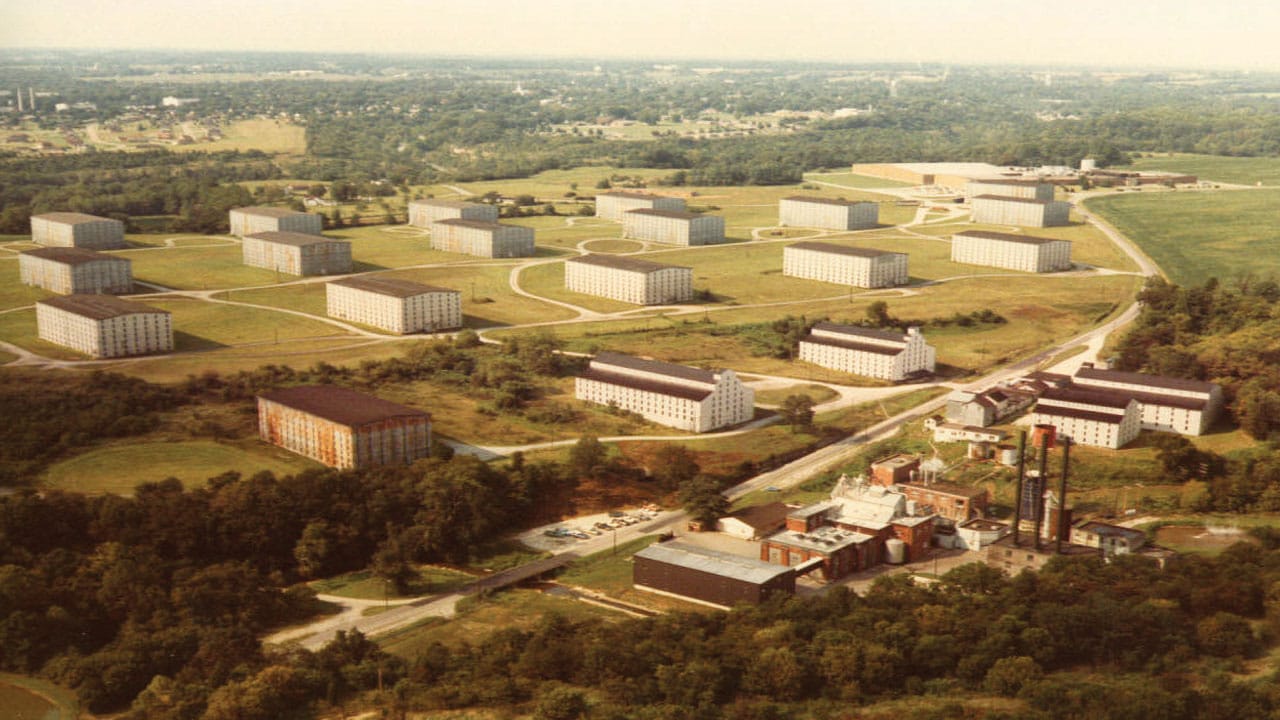

Parker Beam, Master Distiller at Heaven Hill until his death in 2017, loved whiskey aged in our Deatsville rickhouses, among the oldest in our operations. But just two years into aging whiskey in our Cox’s Creek location, the site of our largest and newest rickhouses, Sonne reports that the whiskey from there has exceeded expectations. “Both locations get great air circulation,” Sonne says, adding that the elevation of the Cox’s Creek site aided in its selection.

LOW-TECH STORAGE

According to Blincoe, rickhouse structures have changed very little over the past century for one main reason: the design works. The basic structure is essentially the same, though now often much larger.

Prior to the new millennia, most rickhouses held between 18,000 and 22,000 barrels. But amid the American whiskey boom, distillers have increased production so profoundly that companies like Buzick are racing to build rickhouses holding as many as 58,000 barrels.

A little math to help you grasp these new rickhouses’ increased capacity: If a 20,000 barrel rickhouse was filled from empty to capacity in a single day, the full load of whiskey and barrels would weigh 10 million pounds. For our 55,000-barrel houses, the combined weight of whiskey and barrels soars to 27.5 million pounds.

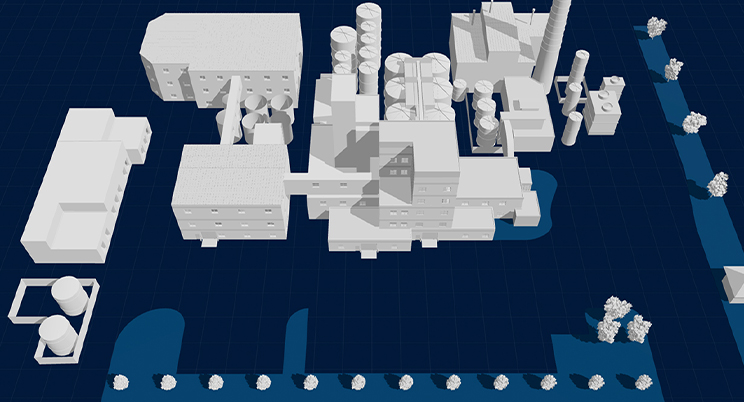

To date, two larger rickhouses have been built at Heaven Hill’s main campus, and seven are in service at Cox’s Creek. Four more are slated for construction at Cox’s Creek, which will house 605,000 barrels once complete.

INNOVATION MEANS WE CAN GO BIGGER

Why didn’t distilleries build larger rickhouses before? Safety codes limit rickhouses without fire suppression systems to 22,000 barrels. So, to avoid the cost of sprinklers, most have opted to build a greater number of smaller rickhouses. Now, however, with the pressure to age more whiskey to meet global demand, distilleries are spending the extra money on fire suppression.

“If you look over there, you can see a 300,000 gallon water tank,” Mike Sonne says on a guided a tour of the Cox’s Creek Barrel Preserve. “Next to that are two pumps that feed 2,500 gallons of water per minute into the system.”

Inside a Cox’s Creek rickhouse, Sonne points out a few innovations. The structure has many more windows (for better heating) than older houses, in addition to motorized “kickers” positioned into the floor of the barrel elevator. At the push of a button, steel arms gently push barrels off the elevator floor and into the rickhouse aisles where workers maneuver them to the ricks by hand.

“Barrels are heavy, so this is really nice,” Sonne says. “Buzick created it for us, and now everybody wants one.”

THE BUILDING BOOM

The American whiskey boom has resulted in a subsequent rickhouse building boom, and Blincoe says the increased opportunity to build more has improved his company’s skills for building and sourcing raw materials.

“We now design building structures knowing where certain woods can and can’t go for the best long-term use,” Blincoe says. “We use a variety of wood species knowing which is best for which member of the building.”

During his 38 years with Heaven Hill, Mike Sonne witnessed the doldrums of the American whiskey industry in the 1970s and 80s. The explosion of rickhouse construction still amazes him.

“That everybody’s jumping in with both feet now … it’s so exciting,” Sonne says. Gesturing toward the skeleton of a new rickhouse under construction on the Cox’s Creek campus, he adds, “Without the boom, you don’t have these buildings going up everywhere. We’re in an amazing time right now.”