The story of cocktail culture in the United States is a curious one. Originally, most enjoyment of spirits was happening exclusively outside the home. The “birth of the bar” began in 1832, when Congress passed the Pioneer Inn and Tavern Law. For the first time in US history, it was legal to sell alcoholic beverages without a customer needing to lease a room for the night. A boom in building public houses and saloons quickly followed, and it was in these rooms that many of the standard cocktails we know and love today were developed.

But, beginning in the mid-20th century, we see a shift towards the home bar, and with it, the concept of a cocktail became one of two things: 1) either the tropical tiki drinks of the “swinging bachelor pad” era, inspired by American G.I.s bringing back the cultural touchpoints of the South Pacific following World War II; or, 2) the very simple spirit + mixer combos that came along with the convenience age that brought us microwave TV dinners and electric can openers.

Lynn House, cocktail expert and National Spirits Specialist and Portfolio Mixologist for Heaven Hill, says that by the 70s and 80s, most cocktail programs at bars and restaurants were simply reflections of what people were making at home. Menus were standardized. Prolific magazine advertising became a huge influence on America’s drinking habits, and bars were stocked with the basic bottles that consumers were being sold at their local liquor store. In essence, most beverage programs were the same.

“That all changed with Dale DeGroff,” says Lynn. “In 1987, Joe Baum offered Dale Degroff the opportunity not only to manage the Promenade Bar at the Rainbow Room in Rockefeller Center, but curate its entire cocktail program. In Dale’s words he was offered the unique opportunity to create a bar in the old style.’ Baum was committed to a “gourmet” approach to cocktails, incorporating high-end spirits, forgotten spirits, bitters, and fresh juices. With this directive, DeGroff looked to the pioneers for inspiration, such as Jerry Thomas’s How to Mix Drinks or The Bon-Vivant’s Companion, written in 1862. Understanding the basic construction of cocktails and sours would be a game changer in Dale’s career.”

Elsewhere, others were leading the charge. Bartenders like Gary Regan, Bridget Albert, Tony Abu Ganim, Audrey Sanders, Steve Olson, and Francesco Lafraconi were pushing the craft forward and creating cocktail programs that were unique and specialized, much like the food menus at the restaurants they were based in.

This impacted cocktail culture to in two distinct ways: first, it gave rise to the concept of the “celebrity bartender.” Lynn remarks that “these early firestarters all went on to become teachers in the world of spirits and cocktails and had many disciples. So, we get this idea of a ‘star’ bartender… much in the vein that star chefs became a topic in society. Consumers were paying attention to what these ‘Barsonalities’ were doing and for the first time, what was happening in bars and restaurants began to influence what spirits people were buying and which recipes they were making at home.”

But more importantly, this shift produced a revival in the interest in classic cocktails, inspiring bartenders to take a more in-depth look at exactly why recipes like the gin martini, Old Fashioned, or Sazerac became such standards. Bartenders were no longer simple technicians, but scholars and craftspeople who understood the history of cocktails and the science behind how the ingredients interacted to produce something so balanced and delicious.

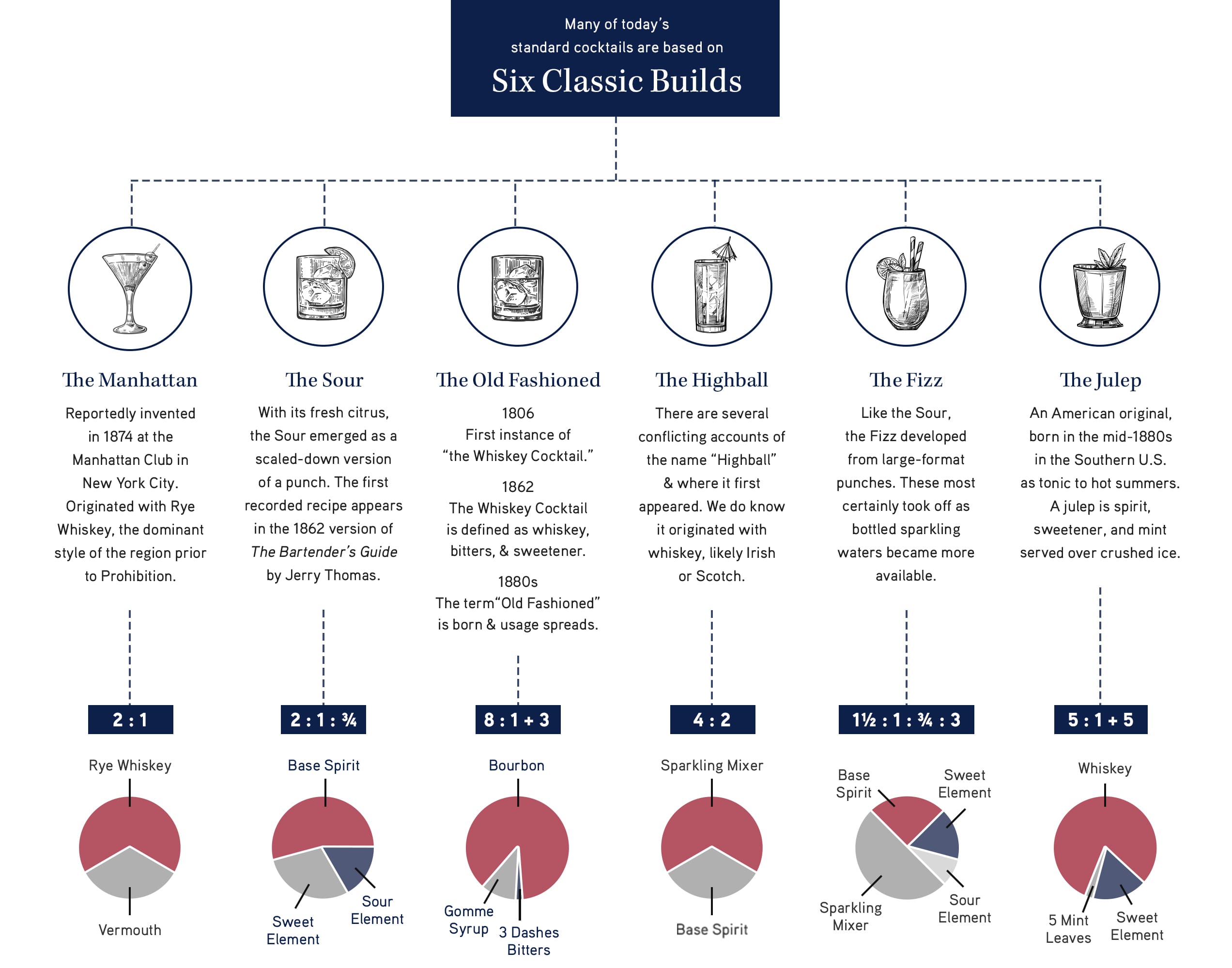

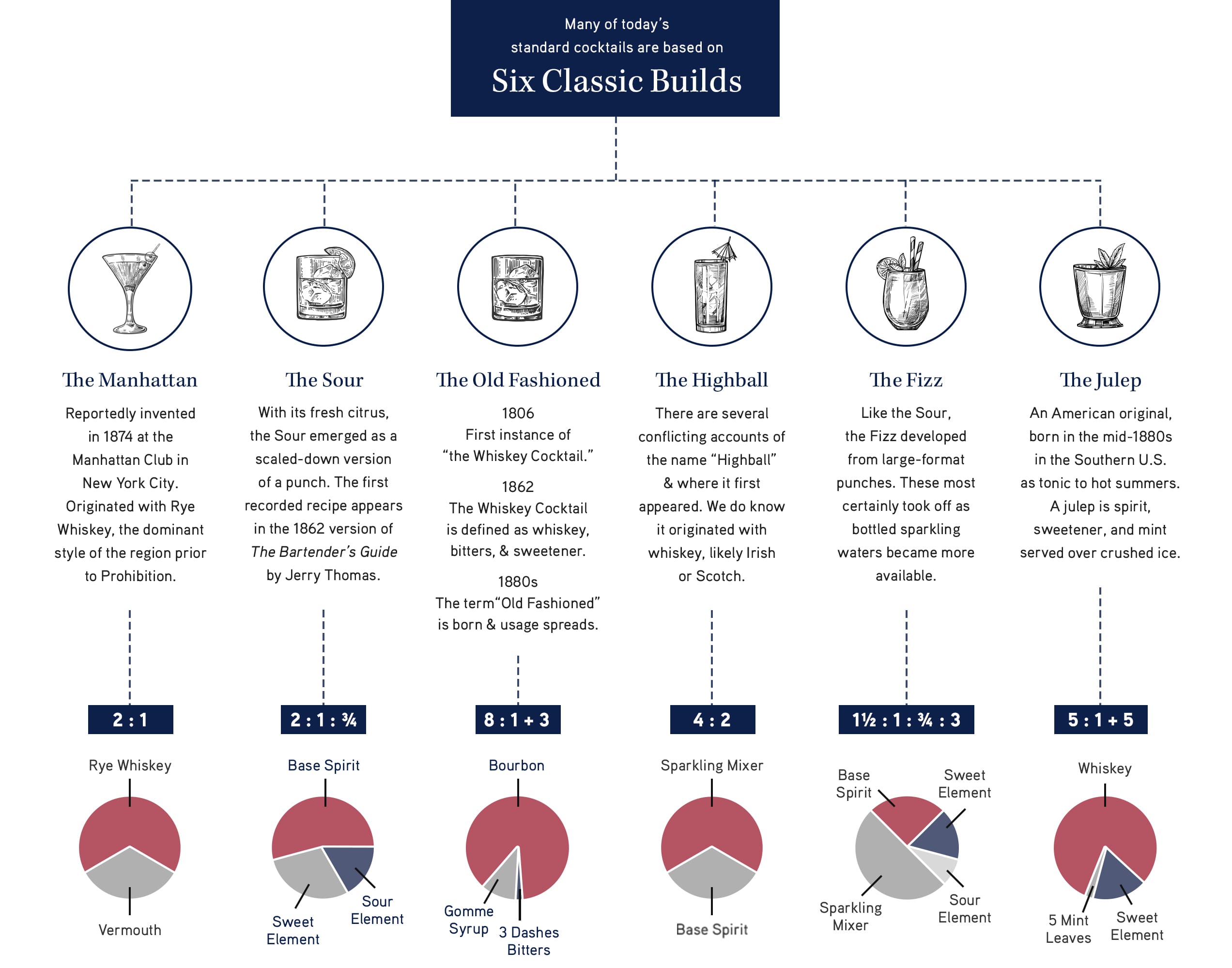

“Cocktail books from days gone by became the favorite reads of bartenders,” says Lynn House. “Things like Harry Craddock’s The Savoy Cocktail Book or The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks by David Embury became the sacred texts of the movement. Jerry Thomas’s The Bartender’s Guide came out in 1862, and it’s there that we find the first documented recipes for the Sour, the Fizz, and the Flip. More than 150 years later, these recipes still work…”

This resulted in cocktails like the Manhattan, Martinez, Old Fashioned, Vieux Carre, and the Cobbler becoming staples on bar menus across the country. As it happened, the American palate also began to mature, shifting from the strictly sweet drinks from 80s and early 90s to appreciating bitters, acid, tannins, and higher proof. Cocktails were designed to highlight the spirits in the glass, rather than mask them with sugar and purees from the blender.

And so, we find ourselves today still enjoying this revival and new golden age for cocktails, complete with enthusiastic consumers. Whenever Lynn asks American Whiskey fans what kind of cocktail they’re interested in making at home, the answer is the same: Classic recipes, prepared well, using ingredients they can keep on hand for whenever the moment strikes.

“Most importantly,” Lynn emphasizes, “they want these drinks to actually taste like whiskey. If there’s Bourbon in it, they want to play off the corn, vanilla, and caramel flavors of the Bourbon. If it’s, say, a rye Manhattan, that spicy, robust flavor is there to complement the sweetness and herbal qualities of the vermouth.”

View the infographic

To teach American Whiskey fans more about some of these classic cocktails and easy-to-memorize recipes, we created an infographic that walks you to through the history and standard ratios. Once you understand the basic balance of spirits to sweet, sour, and bitter ingredients, you can then begin to try different variations that best highlight your favorite whiskeys.

“More than anything, I like to teach people the basic proportion of ingredients that you can memorize or keep handy next to your home bar, and then you can actually make several drinks from the same recipe. The best example is the highball. If you can remember that the simple ratio is two parts spirit to four parts mixer, you can make all the “something & something” cocktails: gin and tonic, rum and cola, scotch and soda. In the Bourbon world, this gets you the Highball cocktail, the Bourbon & Seven, or the Whiskey Ginger… which, when I teach, I always recommend a wheated Bourbon like Larceny to make the ginger beer shine. Add a squeeze of lime, and you have a Kentucky Mule, which is hard to beat in the spring and summertime.”

To learn more about some of these classics, watch Lynn show you how to make a Rittenhouse Rye Manhattan and Whiskey Smash with Larceny Wheated Bourbon in our previous video series.

See Our History of Cocktails Infographic