Over the last ten years, “The Bourbon Boom” has produced a terrific and terrible dichotomy. More people than ever are enjoying America’s native spirit, with a rich culture of fans and festivals to celebrate it.

But many Bourbon fans also are frustrated. They read of distilleries expanding production and warehousing, yet their prized pours seem harder to find and pricier than ever. They understand that strong demand creates product shortages, but with record numbers of barrels being filled, some are left to wonder how a shortage can exist.

The world of Bourbon is in a complex place right now. These are the realities of enjoying American Whiskey in the current era:

- People are consuming more Bourbon than ever, and distilleries are rushing to distill more spirits, and build more rickhouses to age it

- The whiskey news cycle never stops, and readers and podcast listeners continue to gobble it up.

- Bourbon fans have raised the spirit’s profile and desirability via innumerable internet forums and social media posts

Yet… within those same social channels and elsewhere, illegal Bourbon sales have thrived for years, and their impact on legal market pricing is profound.

When Bourbon Was Humble

Over three decades between the 1970s through the 1990s, Bourbon wasn’t as cool, craved, or collectible as it is today. Most spirits lovers sipped cocktails of vodka, tequila, and gin, while others quaffed from the surging tide of American wines and craft beers. Bourbon spent more time on retailer shelves, acquiring dust. (Ironically, it was many of these same dusty bottles that began to fuel the secondary market.)

By the first decade of the new millennium, Bourbon was finding its groove again, quietly regaining its historic relevance and enjoying a newfound popularity. Drinkers wanted bottles new and old, whiskeys subtle and bold, and they were excited to share those liquids and the stories behind them.

“When I got into Bourbon around 2007, it wasn’t about who had what bottle or how many, it was about sharing it,” said Justin Thompson, co-owner of Justins’ House of Bourbon, a two-unit Lexington-based spirits retailer specializing in buying and selling vintage whiskeys. “People would get together with three or four bottles of their own and say, ‘You should try this!’”

While hunting for whiskey years ago, Thompson and a friend spied a coveted Bourbon in a rare decanter bearing a retail price of $400. They had the money to buy it but instead spent that same amount on seven other bottles.

“A few months later I saw people paying $900 to $1,000 on Craigslist for that decanter bottle,” Thompson said. That bottle, he added, “is worth something like $10,000 on the secondary market now.”

When Tom “Fish” Adams began dusty hunting in 2007, he drove the backroads of Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois, and Missouri and stopped at every liquor store that his itinerary would allow.

“So many little stores all over had owners who didn’t know what (good bottles) they had,” said Adams, co-owner of Barrel & Bond, vintage whiskey bar in Paducah, KY with about 1,200 bottles on its shelves. “There’d be an old lady behind the counter saying, ‘I’m just happy to get rid of them. Take what you want, baby.’ And I’d take all she had.”

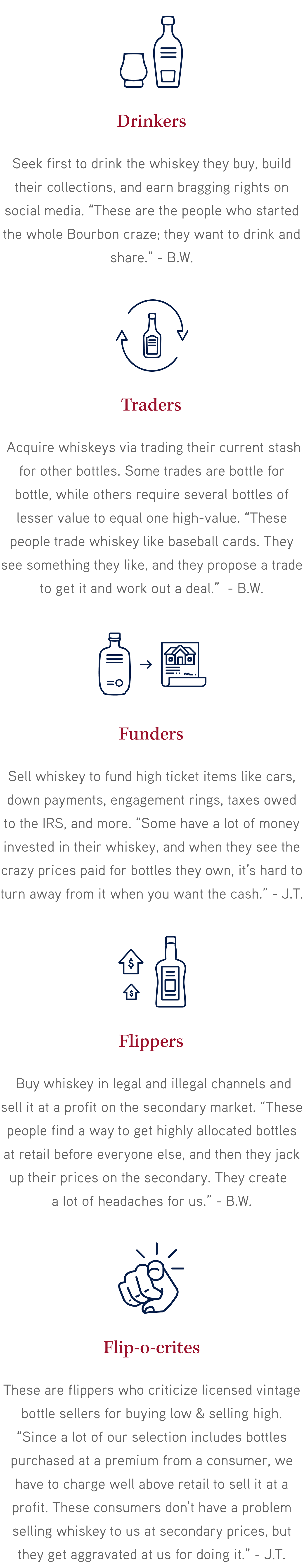

Five Types of Secondary

Market Buyers

As described by Brad Williams and Justin Thompson

The Hunt Goes Virtual

Simultaneously, a market for coveted Bourbons was growing on eBay. Though the online mega-retailer wasn’t licensed to sell beverage alcohol, vintage whiskeys changed hands under the assumption that purchasers wanted the bottles, not the whiskeys within.

“The rule was, ‘any contents are incidental…’ which everyone knew wasn’t legal,” said Bill, a still-active secondary market user who requested anonymity. “When eBay shut down those sales, it pretty much moved to social media, which was much easier” due to direct messaging.

The short answer to the legality question is: yes, the secondary market is illegal for both parties involved. All legal alcohol sales require a seller licensed by the state, and a buyer may only purchase from a licensed seller in the state where the transaction occurs.

The penalties are unique from state to state, but in Kentucky: a first time violator could get a Class B Misdemeanor, up to $250 fine, and 90 days in jail. Repeat offenders could face a $500 fine and up to 12 Months in jail.

As Bourbon buying and selling groups popped up on sites like Facebook, buyers everywhere began learning about American Whiskey. Internet discussion groups created a virtual mountain of free Bourbon information, and its popularity soared. The drawback was that secondary market prices began rising. Bill, who entered the game swearing he’d only drink his Bourbon purchases, said he was amazed at the “stupid prices being paid for whiskeys that cost me very little.” So, when a necessary and costly home repair arose, he became a seller.

“That was never my intention, but it was an easy way to pay for something I had to fix,” said Bill, who has roughly 400 bottles in his collection. “When your purchasing outpaces your consumption, all of a sudden you’ve got a pretty good stash of bottles you’re more willing to sell for crazy prices.”

Bourbon Pricing in the Three-Tier System

The United States liquor market is a three-tier system made up of suppliers (distilleries), wholesalers, and retailers. In “open states,” each tier is made up of individual businesses. In “control states,” the wholesale tier and sometimes the retailer tier is run by state governments.

Ideally, it works this way: Distilleries charge a certain price per case to a distributor, knowing that it will be marked up twice before reaching the consumer: once by the distributor, and then again by the retailer. With these increases in mind, the distillery negotiates a fair price with the distributor. After the whiskey leaves their production facilities, distilleries have little to no control over how those products are priced at retail, though most retailers stay at or within range of SRP on most products. In control states, wholesale and retail prices are generally set by the state and consistent across all outlets.

But amid the Bourbon boom, pricing is increasingly fluid, especially at smaller liquor stores. Lacking the buying power of modern multi-location liquor retailers, smaller retailers struggle to operate profitably without charging more than their large competitors. Many retailers make modest markups over SRP, but as Heaven Hill Communications Director Josh Hafer says, some take it to extremes. When pouring Bourbon at a festival some time ago, Hafer was asked by an attendee for the SRP of an Elijah Craig Barrel Proof he was sipping. When told the price was $65, Hafer says “The guy said, ‘That’s awesome! I’m clearing $175 on these bottles at retail!’”

Outside events such as industry awards also influence retail prices. When Henry McKenna 10-Year Single Barrel Bottled-In-Bond won Best Whiskey at the 2019 San Francisco World Spirits Competition, prices jumped immediately from its SRP of $35.99 to as high as $80 at many retailers. The consumer run on those bottles also moved the brand from “plentiful most everywhere” status to “allocated” due to market shortages. Eventually, some accused Heaven Hill of leveraging the award to price gouge customers when the distillery had not changed the SRP.

“What consumers don’t know is that our timeline to get a price increase into the marketplace is a lot longer than the retailer’s,” said Susan Wahl, Group Director at Heaven Hill. “The retailer might double the price overnight, but if we increase a price, it takes at least six to 12 months to take effect.”

Wahl shares that the SRP changes take so long because product pipelines are filled months in advance of actual sales. And even then, changing the price on a product suddenly made popular isn’t a quick process at a company the size of Heaven Hill, she added.

“We’ve definitely seen where retailers really raised prices to a point we never thought we’d see on a particular product,” Wahl said. “Ultimately, it’s flattering. And that they priced it to that level and someone purchased it demonstrates there was a value for someone.”

The Secondary Market & Three-Tier

System at Work

A Bourbon distillery sells bottles to the distributor knowing the price will be marked up by the distributor and the retailer before reaching the consumer. For a product like Henry McKenna Single Barrel, the on-the-shelf prices vary wildly around the country due to how much the retailer charges and other factors such as taxes and freight.

Special Releases = Premium Prices

Where Heaven Hill and other distilleries begin with super-premium prices is on special releases. Since such bottles are more costly to make and released in smaller quantities, their SRPs can be more than five times as expensive as mainline products.

At retail, bottles such as the Parker’s Heritage Collection are commonly marked up well above SRP because of high demand and limited supplies. And on the secondary market, such prices are often much higher.

“If you’re a retailer who only gets one or two bottles of something special, you can’t help but think like a reseller on the secondary market,” Wahl said. Retailers are thinking, “‘I might as well get what I can get from it.’ And you really can’t blame them for doing that.”

But not all limited releases come with premium prices, said Kate Latts, Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer for Heaven Hill.

“For something like Elijah Craig Toasted Barrel, which we recently released, we want to keep the price somewhere within the equity of the brand’s franchise,” Latts said. Shortly after its summer 2020 release, some retailers had marked it up from its $49.99 SRP to between $59.99 and $99.99.

Brad Williams, vice president of purchasing and product development at the 17-location Liquor Barn chain in Kentucky, said retailers used to be more excited about special releases and allocations. But as supplies have shrunk and customer interest has surged, they’ve become a bit of a headache.

“I [used to] get 30 cases of an allocated product two years in a row, and then it drops to half that because a distillery wanted to put more of that product in other states,” Williams said. “And since customers now know when these things are coming out, they’ll call us constantly to ask if we have them. And if we don’t, they’re disappointed.”

And, of course, where allocated and special release bottles go, hunters and secondary market flippers follow. Some visit stores and buy certain Bourbons so routinely that Williams said staffers know who they are. Those same customers also are regulars in line for special releases.

“Some of these secondary guys—finding those bottles and flipping them is a job,” Williams said. Before the coronavirus pandemic halted the gathering of crowds for special releases, Williams said flippers would pay people to wait in line for them until they could go inside the store and pick bottles personally. “We call those ‘line mules.’”

Like their open-market peers, retailers in control states have long used lotteries to control crowds and sell limited releases as fairly as possible. For the 2020 Van Winkle limited-release lottery in Pennsylvania, the state received 145,000 valid entries for just over 1,800 bottles. In 2019, its Buffalo Trace Antique Collection limited-release lottery received more than 57,000 valid entries for just over 1,900 bottles.

“The good news for consumers in Pennsylvania is that we keep our prices reasonable and far lower than the secondary markets we see in other states,” said Shawn Kelly, press secretary for the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. “Entrants also must have a Pennsylvania address, so products allocated for Pennsylvania can be purchased by Pennsylvanians.”

In North Carolina, where liquor sales are controlled by its Alcoholic Beverage Commission, lotteries are used along with first-come, first-served opportunities that include bottle purchase limits. Public affairs director Jeff Strickland believes the system serves the entire state well, not just larger cities. The biggest perk, he said, is prices remain affordable for everyone.

“I do think we do a good job of getting product throughout the state, but it’s never enough to meet demand these days,” Strickland said. “When we get calls from hunters asking where products are going to show up, I encourage them to get to know their local store operator.”

Reputation is More Important than Price Increases

Some at Heaven Hill will admit that seeing these sky-high retail and secondary market prices on some brands does make them wonder whether they’re leaving money on the table. But they say the urge to react by raising prices is easily tempered when the group revisits some of the company’s long-held beliefs.

“You can ask, ‘What would it do if we raised the price of Elijah Craig Barrel Proof to $100?’” said John Smart, Vice President of Sales and Strategic Partnerships at Heaven Hill . “But then you also have to ask if that’s the brand image we’re even trying to portray. It’s not just about dollars, it’s also about the perception of who we are as a company.”

The company’s chief financial officer, Allan Latts, said high secondary market prices say more about niche and impulse buyers than all Bourbon buyers. Monitoring an illegal market, he added, also provides a poor benchmark for prices on such a wide range of beverages as those held in Heaven Hill’s portfolio.

“You can’t assume that because there is a certain percentage of consumers who would pay those prices, that all consumers would, too,” he said. “Where the supply is very limited, you’ll always have a small group who will pay crazy prices to get it.”

Wahl said that while high prices on some products do add to their premium market perception, overpricing middle-market products risks the wrath of consumers made price-conscious by the internet. Ultimately, the risk of alienating customers with subjectively high prices isn’t worth it.

“Now you have the Overpricedbourbon page on Instagram, where they’re taking pictures of high prices at stores and calling out retailers for it in social media,” Wahl said. “That’s the Bourbon market today. Consumers are getting savvier.”

Ultimately, with the years of aging required and foresight needed to plan for the right amount of mature barrels years and even decades from now, Bourbon has always been about the long game. Maintaining the right relationship and fair expectations with the whiskey community will always be more valuable than making a few extra dollars here and there. As Heaven Hill celebrates its 85th anniversary this year, that long history serves as a reminder of the right perspective. We’re not making and pricing our Bourbon for tomorrow, but investing in how we can help Bourbon fans enjoy whiskeys they love for 85 years in the future.