When Square 6 Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey was released in June, it marked the creation of our seventh wheated spirit—a tasty sipper like none other.

It utilized two mashbills distilled in our pot stills at the Evan Williams Bourbon Experience in downtown Louisville: our Old Fitzgerald Distillate (OFD), compiled of 68% corn, 20% wheat and 12% malted barley, and a brand-new mashbill of 74% corn, 16% wheat and 10% malted barley.

After barreling and aging each distillate separately, each was blended into a 105-proof, highly limited Kentucky-exclusive release. With aromas of caramel, vanilla, figs and bing cherries backed by flavors of confectioners’ sugar, walnuts and cola on the palate, this new Wheated Bourbon is a testament to our respect for tradition and drive to innovate.

“Creating that Bourbon was a lot of fun for our team,” says Jodie Filiatreau, artisanal distiller at the Evan Williams Bourbon Experience. “To think that in one company’s portfolio, we have whiskeys created more than a century ago and others that are brand new. I feel pretty lucky to be involved in that.”

By now, you get the idea that we’re proud of this new release, and all our wheated brands. But you may also be wondering about the differences between Wheated Bourbons and Wheat Whiskeys, their histories and why they’re so popular. Read on to discover wheat’s many roles in whiskey making.

A WHEATED HISTORY OF BOURBON

Wheat’s valuable function in food is amazingly varied and stretches over centuries, but the part it plays in American distilling is less discussed and not as storied. According to Michael Veach, whiskey historian and author, Kentucky whiskey recipes using wheat date back to at least the early 1800s, but they were outnumbered by those combining corn and rye and remain so today.

“Wheat was always around and grew widely in Kentucky,” Veach says. Distillers who chose it likely did so out of convenience “and as a matter of preference—though we don’t have any records saying exactly that. A mashbill was like any recipe. The ingredients people put into it were generally the ones they liked.”

In 1849, wheat made its commercial debut in whiskey made by William Larue Weller. Legend has it that he preferred wheat over rye, and the enduring success of Weller’s brands prove customers enjoyed it also. Another notable Wheated Bourbon fan was John E. Fitzgerald. His story unfolds like this:

Fitzgerald was a bonded U.S. Treasury agent with access to whiskey rickhouses. Using keys meant only for work, Fitzgerald visited those houses surreptitiously and thieved whiskey from barrels and into his own jugs. As the tale goes, Fitzgerald’s visit to those barrels was so frequent that when it came time to dump their contents, the casks were surprisingly light. That led to them being nicknamed “Fitzgerald barrels.”

To honor the Fitzgerald legend, years later, S.C. Herbst created a Bourbon named Old Fitzgerald. As Prohibition ended a few decades later, Herbst sold the brand to Julian P. “Pappy” Van Winkle, who made it the flagship whiskey of his Stitzel-Weller Distillery in Shively, Kentucky. (To this day, the nine-decade-old distillery’s brick smokestack remains emblazoned with the Old Fitzgerald name.)

Despite joining Stitzel-Weller’s other famous “wheater,” W.L. Weller Bourbon, Van Winkle wouldn’t mention wheat’s presence in those mashbills. Decades would pass before his company added the phrase, “a whisper of wheat,” to ads for Old Fitzgerald and W.L. Weller.

“As the story goes, you’d walk into the Stitzel-Weller distillery and see a grain hopper labeled ‘rye’ because they didn’t want people to know they were using wheat,” says Bernie Lubbers, National Brand Ambassador at Heaven Hill Distillery. “But that comes to an end when Julian Van Winkle gives Bill Samuels his recipe and yeast to make Bourbon at Maker’s Mark.”

When Maker’s Mark proudly marketed its Bourbon’s wheat accents, Lubbers says Old Fitzgerald and W.L. Weller eventually did the same.

In 1972, when Bourbon sales were plummeting, Julian Van Winkle, II, sold his father’s company and Old Fitzgerald to Norton-Simon. Not long after, Distillers Limited Co., took ownership of the Stitzel-Weller distillery, and a name change to United Distillers followed.

In 1999, United Distillers approached Heaven Hill about buying its then-state-of-the-art Bernheim Distillery in Louisville, Kentucky. Needing a distillery to replace its Bardstown distillery that was destroyed in a fire three years before, Heaven Hill agreed to the purchase, which included the Old Fitzgerald brand and its remaining barreled stocks. The historic Wheated Bourbon brand has been produced there continually ever since.

THE ‘SOFT’ SELL OF WHEAT

Wheated Bourbons are commonly billed as soft, approachable and sweet, descriptions that are arguably fair. Without rye’s invigorating aromatics and tongue-tingling texture cues, a sip of Wheated Bourbon, especially those commonly proofed into the 90s, glides effortlessly across the palate toward a gentle finish.

Good examples of this include our Larceny Small Batch Bourbon, bottled at 92 proof, and even at 100 proof, Old Fitzgerald Bottled-in-Bond Bourbon is an easy drinker for most. Add to those our easily approachable 90-proof Bernheim Original Wheat Whiskey.

But should wheat get all the credit for a spirit’s softness, or does modest proof play a role?

Let’s compare: Larceny Barrel Proof, voted 2020 Whisky of the Year by Whisky Advocate, ranges from an invigorating 114.8 (Batch A121) proof to Batch C922’s mighty 126.6 proof. Bernheim Original Wheat Whiskey Barrel Proof comes in at a sturdy 118.8 proof, while at 122 proof, the 2021 Parker’s Heritage Collection Heavy Char Wheat Whiskey packs plenty of chutzpah in every pour.

Though high proof, all three remain honeyed and bready, prized and delicious characteristics Conor O’Driscoll, master distiller at Heaven Hill Distillery, credits to their wheat content.

“To me, a Wheated Bourbon tends to have a different mouthfeel with softer, more bready and nuttier notes,” O’Driscoll says. “Think of the differences between cornbread, wheat bread and rye bread. Their mouthfeel and flavor profiles are all different, and that’s likely the same impact those grains have on whiskeys.”

Taking a different line of thinking, Lubbers supposes the absence of rye makes drinkers think wheat sweetens the whiskey. It’s his hunch that in place of rye, wheat’s subtlety elevates the sweetness of corn and the biscuity essence of malted barley.

“I describe wheat bread as the vodka of bread because it doesn’t have much flavor on its own, especially in a sandwich,” Lubbers says. “By not having much flavor, wheat bread lets the flavors of what’s in the sandwich stand out on their own.”

“Compare that to cornbread, which is dense, flavorful and sweet, almost dessert-like. And look at rye bread. When you’re ordering a sandwich, it’s an ingredient all by itself. You don’t just order a ham sandwich, you say ‘ham on rye’ to be specific. You want that rye flavor, texture and spice character.”

Filiatreau returns to the proof argument, saying higher alcohol ramps up wheat’s aromatics and spice notes easily and deliciously.

“Personally, I prefer higher proof, which is one of the things I like best about the Square 6 Wheated Bourbon,” Filiatreau says. “I think a higher proof gives Wheated Bourbon more character. That 105 to 110 proof range is a real sweet spot for me, but trust me, I think Larceny Barrel Proof is pretty awesome at those higher proofs.”

DOES WHEAT AGE DIFFERENTLY FROM RYE?

The legacies of Wheated Bourbon pioneers such as Weller and Van Winkle live on in Bourbon fans’ excitement over the ultra-aged brands bearing their names. Some say the popularity of those bottles placed a halo over all ultra-aged American Whiskeys—and especially so for Wheated Bourbons. Consequently, some now assume that Wheated Bourbon mashbills age better over decades than those using rye.

Andrew Wiehebrink, director of spirit research and innovation at Independent Stave Company, isn’t buying it.

“Based on studies we’ve done, I don’t think grain has the ability to alter the extraction kinetics in the barrel,” Wiehebrink says. “What that means is grains can’t affect how a water and distillate mixture extracts flavor from the barrel.”

Wiehebrink says what raises or lowers extraction rates are known influences such as distillate proof, barrel entry proof, barrel char level, barrel location in a rickhouse—on higher floors, lower floors, near exterior walls or at the center of the house—and, of course, time in the barrel.

“Those premium wheated mashbills that everybody talks about are aged low and slow and on lower floors where temperatures are much cooler,” Wiehebrink says. “The difference between the extractive concentrations happening in barrels on a lower floor versus those on floors five or six are massive—double and triple the difference, in fact. You can age almost anything well in a barrel on a low floor and in the center of a rickhouse.”

Wiehebrink does credit wheat mashbills with their tendency “to retain more distillate character than a rye mashbill. I don’t think wheat distillate is as easily overpowered by wood components as rye.”

O’Driscoll says he didn’t become a true fan of long-aged whiskeys until leading a Wheated Bourbon flight at the Heaven Hill Bourbon Heritage Center (now the Heaven Hill Bourbon Experience) several years ago.

“In the flight was a 15-year-old Wheated Bourbon that I thought would be all woody and barrel forward,” O’Driscoll says. “But it turned out to be one of the most sublime whiskeys I’d ever tasted. Every component was in balance, and it was an example of every part of the process working together perfectly to make something amazing.”

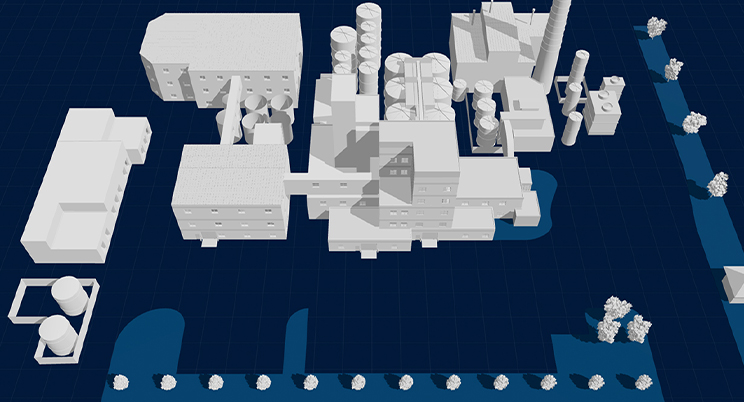

Since aging is a significant part of the overall process, O’Driscoll says that Heaven Hill Distillery barrels are stored according to specific parameters that are uniquely informed by his team’s decades of institutional knowledge. In each of its 65-plus rickhouses located on seven campuses, workers know which locations will condition barrels to suit the flavors of specific brands.

“What’s amazing is the variety we have in our 2-million-barrel inventory and the opportunities that gives us to do so many things with our wheated brands,” O’Driscoll says. “We’ve brought out an 8-year-old Wheated Bourbon because it met our standards for Old Fitz, and we’ve done the same for the 19-year-old. And then there’s that wide range of (proofs we’ve bottled) in our Larceny releases. Clearly, we’ve shown we can manage the same distillate over a big span of years and get fantastic results.”

THE DIFFERENCES: WHEATED BOURBON AND WHEAT WHISKEY

Wheat for Heaven Hill Distillery’s mashbills comes from farms located within a 90-mile radius of Bardstown, Kentucky. Like all our mashbills, that grain is ground on demand, just before cooking.

The changeover from distilling rye mashbills to wheat mashbills isn’t difficult for the crews, Filiatreau says, because “the way we mill and cook either of them, the processes are basically the same. We’ve been doing both for a long time, so we have them down.”

Of course, the difference between a Wheated Bourbon mashbill and that for a Wheat Whiskey is quite a lot. A Wheated Bourbon mashbill must contain at least 51% corn and some percentage of wheat. To be labeled a Wheat Whiskey, its mashbill must contain at least 51% wheat.

There isn’t a rule for the choice of flavoring grains for either mashbill, though corn (for sweetness and body) and barley (for mouthfeel and fermentation) are logical choices for Wheat Whiskey.

Lastly, like Bourbon, to be labeled “straight,” Wheat Whiskey must be aged in new charred oak containers for at least two years.

In the case of our Wheated Bourbons, we have two mashbills:

- Old Fitzgerald Distillate (also used for Larceny) contains 68% corn, 20% wheat and 12% malted barley.

- Square 6 Wheated Bourbon features a blend of the mashbill above and another containing 74% corn, 16% wheat and 10% malted barley.

The Bernheim Original Wheat Whiskey mashbill is quite a bit different, containing 51% wheat, 37% corn and 12% malted barley. Most notably, when released in 2005, it was the first new style of American Whiskey introduced since Prohibition. Aged for 7 years and bottled at 90 proof, it is an easy sipper and perfect in a highball.

In a nod to demand for higher-proof American Whiskeys, we released Bernheim Barrel Proof in 2023. After aging for 7 to 9 years, the first bottling of what will become a semi-annual release clocked in at 118.8 proof. It is bold and grain forward, deliciously honeyed and lightly spiced. Easily sipped neat, it’s the boss in a gold rush cocktail.

FUTURE FORWARD

When asked about the future of wheated American spirits, Veach says the opportunity is huge.

“Just look at all the attention given to every highly allocated Wheated Bourbon out there,” he says. “I don’t see the interest in those bottles going down anytime soon.”

Lubbers pointed to the irony of the outsized attention given to Wheated Bourbons despite their accounting for a smaller share of American Whiskeys than rye Bourbons. Product scarcity definitely plays a role in that popularity, but he says that many whiskey fans are also drawn to the bottomless cocktail of history and hype.

“If we sat here and wrote down all the names of Wheated Bourbons we could think of—just off the tops of our heads—how many could we get? A couple dozen? Maybe a few more?” he says. “What’s crazy is wheated options can’t compare in sales or number to rye options, and yet they’re incredibly popular.”

“The biggest brands in the nation aren’t wheated, but Wheated Bourbons are making most of the headlines. I’m no genius, but to me, that’s a sign that there’s room for those to grow. And that’s great news for our wheated brands.”