Most American Whiskey fans love Bourbon, but a sizable and growing segment of drinkers enjoys Rye Whiskey. In the late 1700s, that latter fact wouldn’t surprise anyone since rye was the whiskey of choice.

Rye grass grew plentifully and was widely cultivated in post-Colonial states like Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. And where there’s plentiful grain, whiskey is made. Along with thousands of farmer distillers spread across the nascent nation, President George Washington operated a sizable rye distillery in Mount Vernon, Virginia.

By the late 19th century, however, widespread and rapid production of corn saw Bourbon exceed rye’s popularity. Its decline would continue unabated for roughly 150 years before bartenders began reviving pre-Prohibition whiskey cocktails. Rye played such significant roles in those drinks that some historians credit it with America’s cocktail comeback.

Why rye? Credit its distinctive spice character. That signature contribution emboldens drinks like the Manhattan, the Sazerac, the Old Pal and others. And in an age when consumers crave bold flavors, Rye Whiskey is ideally positioned to meet that desire and draw others in to give rye a trye.

RYE GRAIN

Rye is a grass (secale cereale) that’s useful to humans when its seeds are dried and ground into flour for breads, beer and whiskey. And agriculturally speaking, it’s a phenomenal cover crop.

“Though above the ground it looks small—about 5 inches tall—rye produces a massive root system,” says Chad Lee, Ph.D., director of the Grain and Forage Center of Excellence Extension and a professor of grain crops at the University of Kentucky. “We’ve gone three feet down and found rye roots that criss-crossed each other. That webbing below the surface prevents soil erosion.”

Lee says rye was grown widely across Kentucky until Prohibition reduced demand for it. Then, as World War II initiated agriculture advances that favored higher-yield crops like corn, soybeans and wheat, Kentucky farmers turned away from rye as a cash crop. Nationwide demand for rye grain didn’t decline, he says, but its cultivation shifted to the U.S. northern plains.

“We don’t know the full story on why rye never came back here like it once was,” Lee says. “But we speculate that skyrocketing corn yields had a lot to do with it.”

Rye is mostly grown as a cover and a forage crop, but it’s also used for the production of flour, beer, and of course, whiskey.

For grain farmers hoping to profit on low-margin commodities, yield (measured in bushels per acre) is keenly important. In a good Kentucky harvest, rye (planted in September, harvested in late June) yields about 55 bushels per acre. Wheat (planted in October and harvested in early June) yields about 85 bushels. Corn (planted in late April and harvested in late September) yields a comparably astonishing 170 bushels per acre.

Since the labor required to grow all three grains is about the same, the incentive to produce rye isn’t as high as it is for corn or wheat (though rye grain typically sells for higher prices than corn or wheat). But with efforts underway like the Kentucky Commercial Rye Cover Crop Initiative (KCRCCI), farmers are beginning to view this vital grain for its cash potential. Knowing that millions of tons of rye are shipped across the U.S.—even imported from Canada, Germany and Poland—to Kentucky distillers demonstrates to farmers that a huge market for rye already exists. Several of them are already experimenting with it, Lee says.

“Some (KCRCCI) farmers are optimistic so far about rye grain yields and feedback from distillers,” he says. “While we’ve seen bushel yield on the low end around 51 to 52 bushels (per acre), distillers are telling us that it hasn’t hurt ethanol yield.”

Heaven Hill Distillery is one of a handful of Kentucky whiskey makers mashing and distilling KCRCCI rye. Conor O’Driscoll, Heaven Hill’s master distiller, says the distillery purchased about 10,000 bushels of Kentucky rye last year, and that most of it was used in the ongoing Grain to Glass initiative.

“Grain to Glass is hyper-local and focuses on a sense of place,” O’Driscoll says, “and the Rye Cover Crop Initiative positions Heaven Hill as a guarantor of a market for farmers willing to grow rye. Ten-thousand bushels of rye is but a fraction of what we use, of course, but it’s a huge portion of the rye grown in Kentucky for distilling. We plan on continuing to support that initiative and purchase even more.”

Lee believes it’s only a matter of time before more Kentucky farmers plant rye to supply distillers.

Rye as a cash crop “is a new market that provides them a chance to generate more income,” Lee says. “Also, a lot of our high-end producers are keenly interested in improving soils over time, and they see rye as helping them do that.”

WHY RYE IN WHISKEY?

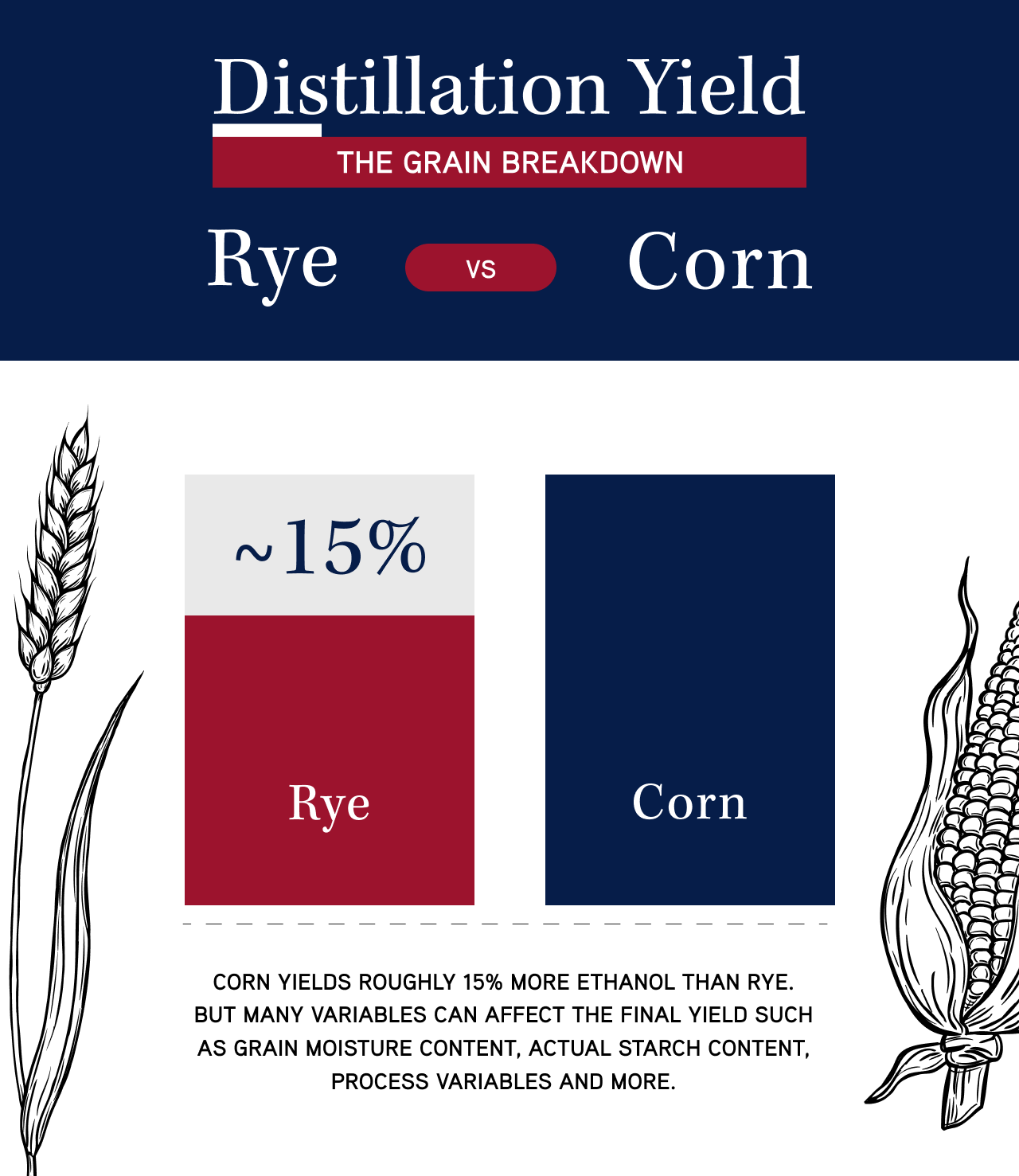

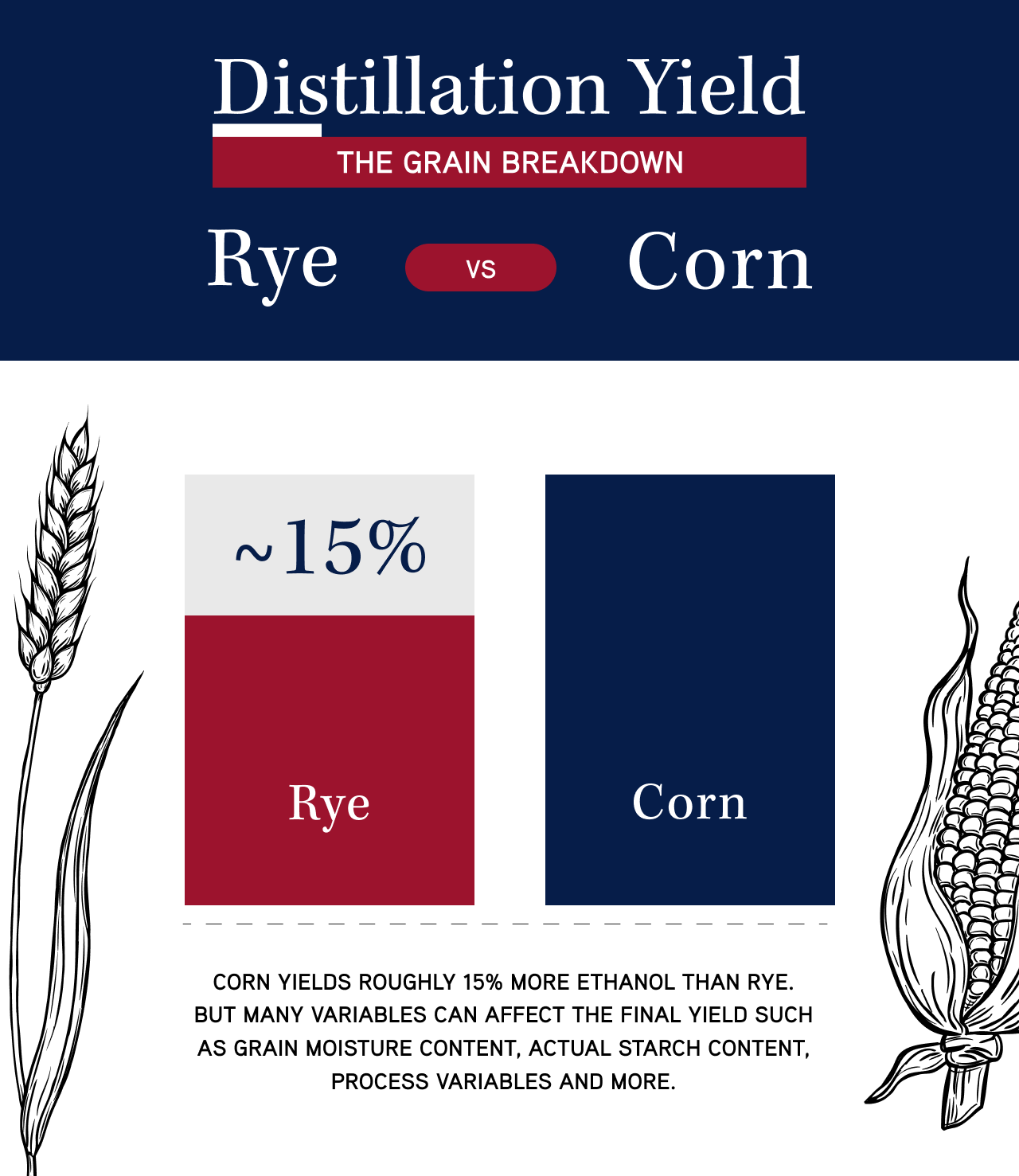

Another way that corn overshadows rye is in its provision of starch content. Starch required for conversion into fermentable sugars that become alcohol is what makes grains valuable to distillers.

“Rye is stingy compared to corn,” O’Driscoll says. “But what it does have is relatively more complex carbohydrates such as cellulose and hemicellulose. When those break down in fermentation, they create those big characteristics rye is known for: rich baking spice and mouthfeel, big cinnamon and nut flavors.”

Relative to flavor contribution, though, rye punches well above its weight. Despite making up just 10 percent of Heaven Hill’s Bourbon mashbill (the remainder is 78 percent corn and 12 percent malted barley), rye’s spice, fruit and candy notes are standout flavors that give our Bourbon backbone and its signature house style. Rye’s spice character subdues corn’s heavier sweet notes while reducing its potentially cloying mouthfeel.

In our Rye Whiskeys (made from a mashbill of 51 percent rye, 35 percent corn and 14 percent malted barley), however, rye flavors move from the supporting cast to starring roles. Simple fruit notes become focused and citrusy. General “candy” accents become cherry and orange hard candy while mint, menthol and grassy notes govern the finish. Place all that into a cocktail, and you’ve got an unforgettable drink with tingle, texture and complexity.

“Put Rittenhouse Rye into a Manhattan and all those flavors jump right through the sweet vermouth,” says Bernie Lubbers, a Heaven Hill brand ambassador. “That it’s 100 proof helps, of course, but even our Elijah Craig 94 proof rye really stands out in a cocktail. Rye’s the boss in a cocktail.”

RYE DISTILLATION: IT’S COMPLICATED

Distillers may love drinking rye, but few like making it, says Abby Long, quality control specialist at our Bernheim Distillery in Louisville.

“The more rye you have in a mashbill, the less that still operators want to deal with it,” she says. “You can’t blame them. Rye’s challenging.”

Long says rye’s curses start with the grain itself. Though finely ground, rye’s thick cell walls resist water permeation. Adding dry rye grain to the cooked corn mash happens gradually to wet it thoroughly and keep it from balling up and clumping as it gelatinizes. Inside the massive cooker, steel paddles attached to a rotating shaft help reduce clumping, but Long says, “If you have rye balls, you’re not getting complete starch conversion, which affects alcohol yields. You’ve really got to have good processes in place to avoid all this.”

Milled grains, including rye, are cooked in small, 35 barrel batches with Kentucky limestone water, in a specified order and at exact temperatures, to create a sweet, porridge-like “mash.”

Rye also is tricky in fermentation: It can be gelatinized and sticky (think of overcooked rice or pasta), and as fermentation begins, its grain particles can rise to the top of the mash and form a dense foamy layer that resists the escape of CO2 produced by the yeast working below. As veteran distillers will tell you, if the gas is blocked, the head can rise and overflow the fermenter. (O’Driscoll insists that when the mash’s potential volume is calculated correctly, the head won’t reach the top.)

Inconsistently cooked rye’s last chance to plague the process happens during distilling. Properly fermented mash is a loose mixture of grain, alcohol and water, and flows easily from its entry point near the top of a column still and down to the bottom where it exits. If any residual, unconverted sugar remaining in the mash sticks to the scalding-hot steam-heated interior of the still, it will scorch. And trace notes of scorching could ruin a batch of distillate and necessitate a shutdown for cleaning. Thankfully, such problems are rarities in technically advanced distilleries.

One final comparison between corn and rye is the big one: yield. Corn yields roughly 15 percent more ethanol than rye.

“People might not think that’s much of a difference,” Long says, “but when you multiply that difference over tens of thousands of bushels, it adds up to a lot.”

OUR PORTFOLIO OF RYES

When it comes to sales, Lubbers points out that domestic Bourbon sales dwarf rye purchases. According to the Distilled Spirits Council of the U.S. (DISCUS), case sales of American rye reached nearly 1.4 million in 2020, while Bourbon case sales approached 26 million that same year. Rye’s growth trajectory, however, is impressive: up 1,275 percent since 2009, according to DISCUS.

“Looks like people are catching on to rye, right?” Lubbers says with a grin. “That certainly bodes well for Heaven Hill.”

An avowed fan of whiskey history, Lubbers lights up when talking about Rittenhouse Rye and Pikesville Rye.

“Rittenhouse is what opened up the door to restaurant and bar sales for Heaven Hill,” he says. “Bartenders wanted it for its Bottled-in-Bond strength, and they wanted a whiskey with a great story.”

[Learn more about the storied past of Rittenhouse Rye Whisky]

Created in 1934 by Continental Distilling as Rittenhouse Square Straight Rye Whisky, the Philadelphia-made whiskey became a regional favorite. But like most American Whiskeys that languished for the final three decades of the 20th century, it didn’t gain national renown until Heaven Hill acquired the brand in 1999.

“With more excitement than ever in the Rye Whiskey category, Rittenhouse gives Heaven Hill a lot of credibility by making us important in the cocktail space,” Lubbers says. “Rittenhouse gives us a sizable piece of domestic rye sales overall.”

Pikesville Rye is an even older whiskey brand. Created in Maryland in 1895, it, along with the rest of the once-booming Maryland rye industry, nearly died off during Prohibition. When Prohibition ended, the brand reemerged as the last standing example of Maryland-style rye (a rye mashbill containing a high percentage of corn). Heaven Hill purchased the brand in 1982 and continued selling a 3-year-old, 80 proof iteration of it until that was replaced in a 2015 relaunch as a 110-proof, 6-year-old super-premium whiskey.

O’Driscoll says his favorite drink is a Manhattan made with Pikesville.

“You’re not fooling around when you choose Pikesville,” he says, laughing. “When I want rye to stand out in a cocktail it was made for, I go with high proof. But I also enjoy it on the rocks.”

Rounding out the portfolio, Elijah Craig Straight Rye Whiskey was launched in 2020 and is made from the same mashbill used to make its rye siblings. This extra-aged rye is rich and complex and clocks in at a comparatively modest but still robust 94 proof. Lubbers explains Heaven Hill’s decision to add a Rye Whiskey to its famed Bourbon line.

“If you look at how product lines grow over time, it’s logical to build a brand family that includes more than just a Bourbon and barrel proof version of that same Bourbon,” he says. “Now we have not only Elijah Craig Rye, we also have Elijah Craig Toasted Barrel Bourbon and an 18-year-old single barrel Bourbon. Together, those offerings build real strength for the Elijah Craig name.”

They also serve to undergird Heaven Hill Distillery’s long-standing commitment to preserving whiskey tradition.

“You know how Max Shapira is when it comes to whiskey history,” Lubbers says, referring to Heaven Hill’s long-time president and soon-to-be executive chairman. “He’s fascinated with those older brands, those neglected brands that, to him, have untapped potential. His enthusiasm for acquiring those and bringing them back to life started as a passion project for him. But for the company, they’ve become some incredible brands and category leaders. That’s the story of our ryes.”